With the war came other changes and new kinds of

hardship - air raids, the blackout, rationing, gas masks and men away fighting.

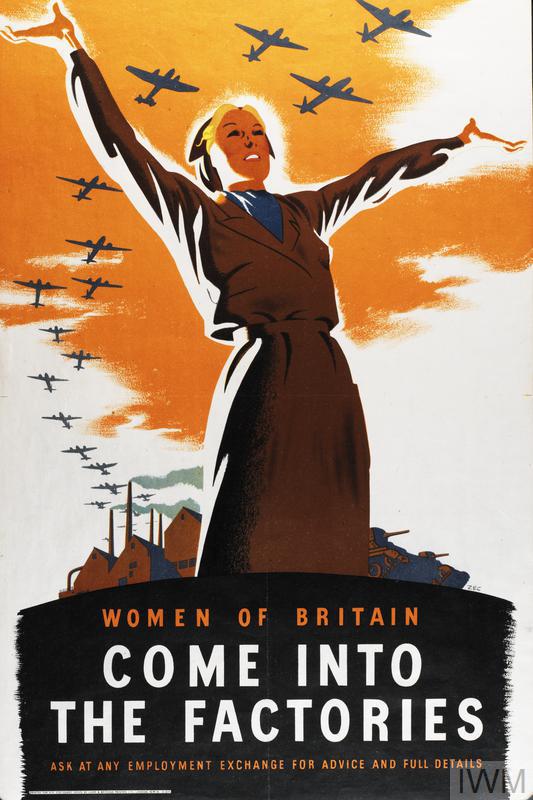

Women were drafted into factory work and homes and family life adjusted as evacuees

from London were made welcome. The Village Hall was used as a school room for the

evacuated children and equipped for use as a First Aid Post and Rest Centre. The

Minute Books of the Institute tell of whist drives and dances organised as part

of the war effort, especially during ‘Wings for Victory Week’ in 1942 and 'Salute

the Soldier' Week the following year. Occasionally the Hall was used for billeting

soldiers and, as in every other town and village, uniforms became part of the pattern

of life. A gun site was established on Dorney Common close to Eton Wick and the

noise shattered many a night's sleep. Eton Wick was lucky, however; a few bombs

did fall on the village, but did very little damage, and the explosion which set

a field alight seemed quite spectacular at the time. Men on active service were

not so lucky; twelve lost their lives as the War Memorial at the church bears witness.

The story of Eton Wick during the war is not much

different from that of any English village, but the 1940s mark a watershed in the

history of Eton Wick. Change has always been taking place, albeit at times almost

imperceptibly; but at this time the changes were to be great and far-reaching. Within

a decade of the end of the war the long straggling rural village with its close-knit

community had disappeared; its place taken by a larger dormitory village, top heavy

with council houses.

The first new houses built were twelve 'prefabs'

on part of Bell's Field. They were meant to be temporary, but instead provided good

if not beautiful homes for more than twenty years. They were built towards the end

of the war, and the first post war houses completed the development of the Bell's

Field Site; the pale pink colour of the bricks is a constant reminder of the shortage

of good facing-bricks at this time. A year or so later Tilston Field (north of the

Eton Wick Road) was bought from Eton College for the first housing estate in the

village itself. Great care was taken over the design of the housing and roads; trees,

shrub borders and a small recreation ground were included to improve the amenities

of the estate. Five fine police houses were built fronting the main road, and the

Council were proud enough of the scheme to enter the completed half of the estate

for the Ministry of Health Housing Medal in 1951. In the following year Prince Philip

officially opened the estate at a small informal ceremony. Meux's Field was also

bought by the Council and here were laid out Princes Close and a shopping parade,

making altogether over two hundred houses and seven shops.

The main road from Moores Lane to Dorney Common

was considerably widened and a shrub border planted in front of the estate and,

as if to mark the change in appearance, its name was changed from Tilston Lane to

Eton Wick Road. There was a zest for rebuilding and not only in bricks and mortar.

Many of the clubs which had sunk into the doldrums during the war were revived and

new ones founded. The first of these was probably the Youth Club which was started

in 1946, followed by the Over Sixties Club in 1947 and a few years later the Parent

Teacher Association, the Unity Players and the Young Wives. The Village Hall was

still the centre of much of the social life of the Wick and great efforts were made

to put it on a sound footing after the war. In 1950 it was redecorated by voluntary

help, electricity was installed and in the following year it was enlarged by the

addition of a covered forecourt. Two issues of a magazine called ' Our Village '

were published by the Institute as it was still sometimes called, and for several

years from 1950 a Village Hall Week was held in the early part of the year. Village

football became so popular that a Minors' Club was formed. When this proved very

successful a second team of young men too old to stay in the minors' team had to

be started. Eventually the club was renamed the Eton Wick Athletic Club and there

was even more cause for 'Up the Wick' to be heard each Saturday.

This is an extract from The Story of a Village: Eton Wick 1217 to 1977 by Judith Hunter.